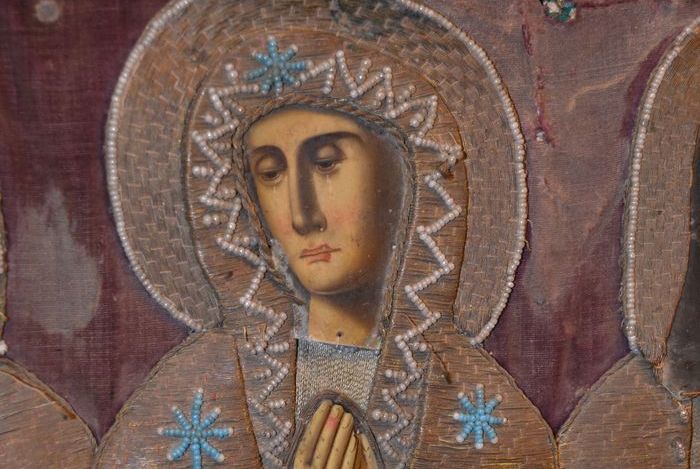

He knew his mother sympathized with these often persecuted people. He had been intrigued, too, by the stories his fellow schoolmates told of strange and horrible rites in which, it was said, the participants drank blood and the most depraved of orgies occurred. But when he and several other boys had crept into the temple one day, after finding the door ajar, they had seen nothing more terrifying than a faded wall painting of a man crucified upon a rude wooden cross, above which had been painted a strange emblem Constantine had never seen before. After that he had dismissed the Christians without another thought, for Mithras and the Emperor were the soldiers’ gods. And when the time came for him to think of such things, he had no doubt that he would follow the traditions of the Roman army.

Constantine remembered noticing two horsemen approaching Naissus from the east just before his attention had been attracted by the roof of the temple. When he looked more closely now, he saw that they were nearing the center of the town and hurried down the hill thinking they might be couriers of the Imperial Post by which mail and important passengers were carried throughout the Empire.

Sometimes, especially when trouble flared on the frontier, he and the other schoolboys would linger after classes at the yard of the inn beside the crossroads, eager to hear the stories told by the dust covered couriers, as they hurriedly ate their meat, bread and wine while waiting for a change of mount. But except for the upstart Carausius, who had seized the province of Britain while Diocletian and Maximian had been busy with rebellion elsewhere, and an occasional sporadic outburst from the peasant rebels of Gaul called the Bagaudae, the frontiers of the Empire were quiet at the moment.

Familiar street in the warm sunshine

As he walked along the familiar street in the warm sunshine, Constantine once again let his thoughts race with his turma, as he led them in a charge. Then a clod of dirt struck his shoulder and he whirled to find himself facing a group of jeering boys, led by an older and larger one. They had obviously been waiting to hem him in where the wall of the butcher shop at his back cut off escape and, engrossed in fancy, he had let them catch him unawares.

Nothus bastard. The largest of the boys spat the word at Constantine, his broad peasant face with its small piggish eyes contracted in a sneer.

“Let me pass, Trophimus!” Constantine ignored the epithet, as his eyes moved from one to another of his captors in a quick scanning glance before coming to rest once again upon the largest boy. In that rapid appraisal he was able to decide that Trophimus was the aggressor as he had been on numerous other occasions and that with him defeated the others would not be likely to intervene.

Read More about Emperor Diocletian at Nicomedia